How a fibreglass show car, initially not meant to be built as a production machine, captured the heart of America.

America’s own sports car is 70. In that lifetime it’s been transformed from an anaemic, auto-only show car to a 200mph plus supercar, lived through 8 incarnations and, like many other American icons, had dozens of facelifts, some more successful than others. It has, however, remained stylish, desirable and, crucially, attainable. As a result, America’s love affair with this resolutely 2-seater sports car has never dimmed; Cobras, Vipers, Thunderbirds, Bricklins and others have come and gone but the Corvette has evolved successfully by staying true to its roots.

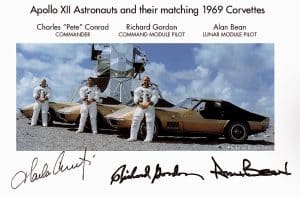

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of the Corvette in American culture. Prince sang, ‘Little Red Corvette. Baby, you’re much too fast’ but his masterpiece of 80s pop is one of a plethora of songs, films and TV shows to feature, or even eulogise, the Corvette. America’s greatest ever real-life heroes, the Apollo astronauts, all drove C3 Corvettes, a brilliant piece of marketing which was initially instigated by the local dealer rather than Chevy’s PR department.

The Corvette’s cultural icon status was highlighted most bizarrely in January 2023 when President Joe Biden was found to have classified documents, from his time as Vice President in the Obama administration, stored in the garage of his home in Delaware.

As the story developed, the US media gradually migrated away from deliberating the issues storing these documents in this insecure location presented, and started discussing just how cool his Corvette is instead!

Because of its iconic status, a Corvette has been the main character car in a host of TV shows including the 1970’s cult series ‘The Magician’, which featured Bill Bixby as Anthony ‘Tony’ Blake, a rich playboy and philanthropist who used his magic skills to solve crimes (a sort of sun-soaked proto-Jonathan Creek). It featured Blake’s white C3 Corvette extensively, usually while he was talking into that 1970s crime-fighting essential, a car phone.

A silver C3 Corvette was the beach-soaked relationship catalyst for Shirley MacLaine and Jack Nicholson’s Oscar-winning performances in ‘Terms of Endearment’ and a Corvette C2 was also the main automotive symbol in everyone’s favourite guilty pleasure action film, ‘Con Air’: “On any day that might seem strange”.

Is anyone now reading this without seeing a Corvette being towed through the air by a plane…?

In hindsight, the Corvette is an enormous success, with an unbroken 70 years of production behind it and over 1.75 million produced, it can’t be anything else. It has consistently raised the image of both Chevrolet and its parent company, GM, whilst making a profit as well; job done. It almost stalled at the first hurdle, however, and was originally only intended to be a show car, EX-122, to be displayed at GM’s Motorama exhibitions. This touring extravaganza opened in New York’s Waldorf Astoria in January 1953 and thereafter travelled around the USA to different locations.

1953 Chevrolet Corvette Mororama Show Car

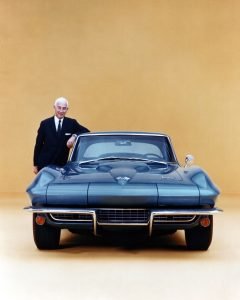

It was dreamt up by legendary GM stylist Harley Earl although actually styled, in the main, by Robert McLean and supported internally by Chief Engineer Ed Cole.

Harley Earl.

All were keen to experiment with the new wonder material, fibreglass, first seen on the low-volume Woodill Wildfire. Both the press and the public alike were captivated by the glorious shape and this new exotic material. GM immediately put it into production but by 1954 the previously euphoric GM executives were ready to pull the plug, people loved it but, crucially, didn’t buy it.

Ironically, the stay of execution came because Ford released the Thunderbird in September 1954 and it immediately outsold the ‘Vette by a whopping 23-1 margin, proving there was a market for a 2-seater car. GM were not to be outdone by their great rival and by this time they had acquired a secret weapon, their new V8, and a man to deploy it, Zora Arkus-Duntov; the father of the Corvette.

Corvette was not a high-performance car until Zora Arkus-Duntov fitted it with a V-8 engine and began campaigning Corvettes in racing in the late 1950s. The late Argus-Duntov is shown with a 1966 Corvette.

Belgium-born, Russian engineer Duntov had worked for Sidney Allard in the UK but resigned in 1952 to seek work in America. He’d stood in the crowd during the Corvette’s Motorama launch and been captivated by it but at that point was unemployed. By May 1953 he’d secured a post as a development engineer at Chevrolet and shortly afterwards landed his dream job, developing the Corvette. He was an enthusiast first and foremost but proved equally adept at both engineering and navigating GM’s internal politics. He oversaw the 1955 Corvette’s transformation into a V8-powered sports car with manual transmission and a more comfortable cockpit. By 1958 the double headlight style and bold colour schemes made the ‘Vette a really attractive car and 9,168 were produced, a record at the time which has since been broken numerous times.

1958 Corvette Convertible

The Corvette grew from there, in both stature and ability, while racetrack success begat the glamourous performance image the car needed.

1960 Corvette Racer 1 LeMans

1960 Corvette at Le Mans

Motor racing has continued to be central to Corvette’s image ever since, with the car scoring numerous victories all over the world.

The Chevrolet Corvette Racing C7.R #64, driven by Oliver Gavin, Tommy Milner and Jordan Taylor, races to victory at Circuit de la Sarthe Sunday, June 14, 2015 winning the GTE Pro class of the 24 Hours of Le Mans United Sports Car Championship, FIA World Endurance Championship in Le Mans, France. It is the eighth Le Mans class victory for the Corvette Racing team since its debut here in 2000. (Photo by Richard Prince for Chevy Racing)

Corvettes also make competitive historic racers and are very much part of events such as the Goodwood Revival.

Duntov’s knack for giving the enthusiast what they wanted, ensured the car’s future was never in doubt again and the best talent in GM produced the first Corvette he felt could go toe to toe with European competition, the 1963 C2, or Sting Ray. That 1962 ‘Vette, styled by Japanese American Larry Shinoda, totally rewrote what a car could look like and still looks avant-garde 60 years later. Although it was a huge step forward, the C2 was aerodynamically very flawed, as Duntov famously said, it had, ‘just enough lift to make it a very bad aeroplane’.

1963 Chevrolet Corvette Z06.

1963 Chevrolet Corvette

1961 Chevrolet Corvette Mako Shark I and 1965 Chevrolet Corvette Mako Shark II

The follow-up third-generation Corvette, or C3, was also styled by Shinoda and borrowed heavily from his Mako Shark concept cars whilst taking the chassis of the C2 almost unchanged. It remained in production, through various updates, until the C4 was announced in 1984

The C2 Corvette team may have had a lot to learn about aerodynamics, but the Corvette chassis had taken a technological leap forward with the 1963 C2, and the design endured, in basic terms anyway, until 1983. It incorporated a lot of what Duntov had learned in racing and although, like the C1, it was still a steel-boxed full frame the C1’s big X-member was eliminated in favour of welded steel rails connected by five ladder-type cross-members that helped make the chassis 90% stiffer. The cockpit was lower and further back, as were the engine and transmission, bringing it closer to a 50/50 front-to-rear weight balance and lowering the centre of gravity. With equal spring rates, the ’63 chassis had a more balanced feel and rolled 18% less than a C1. The front used spherical ball joints and shared parts with production passenger cars. A recirculating ball steering box used a relay-type linkage (mounted behind the front wheel centre lines) and a steering damper was incorporated on cars with manual steering. Power assist was also available for the first time. Duntov and his team were already planning the C3 when the C2 had only been in production for a few months. They had looked initially at a radical mid-engine solution but that made no headway in budget terms, so decided instead to clothe existing chassis and running gear in a new body which actually worked aerodynamically; those small grilles under the bumper of the production C3, added toward the end of the development, transformed the shape by allowing air to get in to cool the car and exit through the side grilles. They also reduced lift as there was no build-up of air under the car to lift it in an almost hovercraft-like way as there had been at 100mph on the C2.

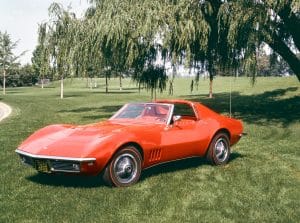

1968 Chevrolet Corvette

1968 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray

Once the aerodynamic and cooling concerns had been sorted Larry Shinoda and the team worked on making the shape timeless and elegant in a way the shocking C2 had not been, meaning the C3 would not date as quickly. Thus, the C3 shape ran from 1968 until 1972 largely unchanged. The longer nose for impact bumpers came in 1972 and the longer impact rear bumper the following year. The fact the basic design lasted until 1983 is partly a testament to the rightness of the concept and partly because the 70s were a troubled and confusing time for the motor industry, which had to divert development resources to meet impending emissions and crash regulations, slowing the development of new cars.

Ironically the Thunderbird had abandoned the 2-seater market for its second generation in 1958 and from then onwards the Corvette has offered more bangs per buck than any other 2-seater sports car in the world. While the early seventies ‘smog-era’ of impact bumpers and low power figures from vast engines was a Corvette’s low point, it was for the whole industry, and the car continued to sell profitably. The Corvette has continued to sell through seven generations and a myriad of mid-life updates but has remained at heart a front-engined rear-wheel-drive fibreglass-bodied sports car sitting on a separate chassis until 2020.

Seven generations of the Chevrolet Corvette. Each generation of the Corvette has been defined by all-new or significantly revised design, architecture and technology features – including powertrain and chassis/suspension technologies – that have helped the car maintain its position as the best-selling premium sports car in America.

Over the 67 years there have been many fantastic special editions and race victories aplenty, plus magazine test victories and losses against its German nemesis, the Porsche 911; it could even be argued the front-engined V8 928 that was initially slated to replace the 911 was inspired by the Corvette…

Perhaps Porsche realised that they couldn’t take on the Corvette head-to-head, but Chevrolet shocked the world in 2020 by taking on the supercar establishment, including Porsche, by launching the first-ever mid-engine Corvette. It still features a V8, of course, but it has taken the ‘Vette into the supercar world in every sector except price. The current mid-engine C8 may well be the last V8 I.C.E. incarnation of America’s plastic fantastic sports car, but who’d bet against an electric Corvette being America’s sports car of choice in another 70 years?

2023 Chevrolet Corvette Z06

Thanks to:

- GM media for Corvette Pics, Ford Media and Stellantis Media for Viper image