Back in the early ‘60s, Ducati was one of dozens of Italian motorcycle manufacturers, struggling to overcome the situation in their crucial home market. From 1955, the tiny Fiat 500 car had sold spectacularly well and brought an end to the post-war boom in Italian motorcycle sales brought about by the war-ravaged country’s need for basic transportation.

In Ducati’s case, production had declined to around 6000 bikes a year by 1960 and the company was only kept afloat thanks to state subsidies. The parlous state of the Italian home market meant an ever-greater dependence on Ducati’s American distributor.

The New Jersey-based US importer of Ducati was the Berliner Motor Corporation which, after its appointment in 1957, was selling no less than 85% of the Italian company’s total production by the early 1960s. This meant that the brothers Joe and Mike Berliner effectively called the shots at the recession-hit Italian company. Elder brother Joe Berliner was convinced of the potential of the US police market, especially since American anti-trust legislation required that police departments consider other options besides the monopoly that Harley Davidson had inherited after Indian went out of business.

Official US police department specifications were increasingly standardised across the country and naturally favoured the overweight, unsophisticated, large-capacity, home-grown product which Harley Davidson had been building since its earliest days. Specifically, the parameters for US police bikes required an engine capacity of at least 1200cc as well as a minimum 60-inch/1525mm wheelbase, and – worst of all – the use of 5.00 x 16 tyres: no other sizes were acceptable.

Although the Italian company’s largest-capacity model in 1959 was the 200cc Elite, Joe Berliner contacted Ducati chief Dr.Giuseppe Montano to see if the firm was interested in producing a special machine for this significant market. Montano and designer Fabio Taglioni readily agreed – especially after considering the design of the archaic 74 cu. in. Harley that was then effectively standard issue to US police departments. They were certain that they could produce a more efficient and much more modern design which Berliner could sell at reasonable cost even after payment of the quite steep US import duty. And engineer Taglioni eagerly accepted the commission as he relished it as a technical challenge.

Montano, however, encountered initial scepticism from the government bureaucrats in Rome who controlled the company’s finances, and this meant that negotiations with Berliner dragged on for a couple of years. Eventually, a deal was finally struck in 1961 resulting in a joint venture, whereby Berliner would underwrite the development costs of the new model. The agreement called for Ducati to construct two complete prototypes and two spare engines.

The Apollo was the result – a name chosen by the Berliners to commemorate America’s manned space flights, which had recently begun. In return for their financial aid, Berliner Motor Corp. would be allowed to dictate the bike’s specifications but, apart from meeting the standardised US police regulations, the brothers’ only stipulation was that the bike should have an engine bigger than anything in Harley’s range, which was then topped by the 74 cu. in./1215cc FL-series Duo Glide.

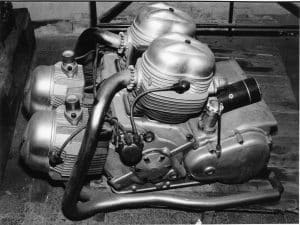

The remainder of the technical specification was left to Taglioni, who decided on a 90-degree V4 engine because it would have perfect primary balance and there would be no need for a crankshaft counter-balancer to cure vibration. This was even the case with the 180-degree crank throws he opted for, which resulted in the ‘big bang’ effect of each pair of pistons rising and falling together.

An integral part of the proposed engine layout was the use of separate, differentially finned, air-cooled cylinders and it used pushrod-operated overhead valve gear with a single gear-driven camshaft positioned centrally in the crankcase ‘vee’ between the cylinders. This was the same layout used on the big American V8 car engines and on the Harley vee-twins. Therefore, US police vehicle mechanics were well familiar with it and could work on that type of engine in their sleep. This was an important consideration in respect of fleet maintenance.

The front cylinders of the mighty 1256cc engine were lifted 10 degrees from the horizontal to improve cooling to the rear pair when the engine was installed in its chassis, which had a central box-section downtube between the front two cylinders.

At just 450mm wide, the all-alloy V4 engine was relatively compact in spite of its architecture and allowed the Italian bike to compare more than favourably with its Harley rival. The Apollo scaled 271kg. dry weight with a 1555mm wheelbase as against the American V-twin’s 1580mm and 291kg.

So, even though Ducati test rider Franco Farne came back from an early test run aboard the Apollo complaining that it handled like a truck, this was accepted as being just ‘The American Way’. And anyway, the Apollo more than made up for this with its straight-line performance.

This was due to its 100bhp at 7000 rpm as against 55bhp for the Harley Wide Glide. Running on four 32mm Dell’Orto SS carbs and with a 10:1 compression ratio, the Apollo was good for a top speed of more than 200km/h – more than 120mph. Hugely impressive for the day and befitting what was in prototype form the largest capacity and most powerful motorcycle yet constructed in post-war Europe.

But ironically, the impressive fact that this was the most powerful motorcycle in Europe was also a damning factor in the USA. Its meaty performance was the Apollo’s downfall – a fact confirmed by Ducati tester and former GP mechanic Giancarlo ‘Fuzzi’ Librenti, who was the first rider to suffer the heart-stopping experience of having the specially made 16-inch whitewall Pirelli rear tyre throw its tread at high speed on the Milan-Bologna autostrada, after ballooning under sustained 100 mph speeds and detaching from the rim.

The 100bhp V4 engine was simply too potent for the 16-inch Pirelli tyres to cope with and it took detuning the engine to produce only 65bhp before this key safety issue was eliminated. This was still adequate to meet US police specifications, and overall performance was still superior to the Harley, thanks to the V4 Ducati’s lighter weight. It appeared to finally resolve the tyre problem.

Unfortunately, while still OK for police bike purchases, this power reduction effectively ruled out the Apollo being sold to the general motorcycling public as a luxury sports tourer and freeway cruiser since its power-to-weight ratio was now inferior to the BMW and British twins which would have been its rivals in the US ‘imports’ market. With the V4 set up to deliver the right kind of power to meet the demands of the sports tourer marketplace, it would, unfortunately, be lethal until tyre technology caught up with it.

This situation provided the perfect opportunity for the Italian government bureaucrats controlling Ducati’s finances to kill off a project they’d never had much faith in. They were able to cite as an excuse the fact that, with the model now suitable only for the specialist police market, its sales would be insufficient to justify the immense tooling costs involved in gearing up the Ducati factory for its production.

The Berliner brothers, who had already successfully demonstrated the Apollo to selected police chiefs, were appalled. They had promised that production of the reduced-power version would commence in 1965, yet now the whole project seemed in danger of collapse.

And so it proved. Further state funding for the Apollo was withdrawn, and without that, Ducati was forced to cancel the project early in 1965. This was no fault of Taglioni’s, however. He had designed a superb motorcycle that would have done just what the Berliner brothers had asked for in terms of American police bike sales potential. But as a bike for the general marketplace, the Apollo was just too much, too soon.

Information and images courtesy of The Motorcycle Files

For more information on the Ducati Apollo V4 we recommend the e-book written by Alan Cathcart for The Motorcycle Filesseries.

We also recommend the print book in the same series also written by Alan Cathcart and titled Dr Desmo – A Tribute to Fabio Taglioni, Ducati’s Design Genius

ALL TITLES IN THE MOTORCYCLE FILES SERIES ARE AVAILABLE DIRECTLY FROM AMAZON